Batman: The Long Halloween #7-13 (May 1997-Nov 1997)

Storytellers: Jeph Loeb & Tim Sale, c. Gregory Wright, l. Richard Starkings & Comicraft

Perpetually in print in trade paperback, plus a hardcover “Absolute Edition,” a special black and white hardcover edition, and a deluxe hardcover omnibus with the rest of Loeb & Sale’s Batman stories. Available for purchase digitally as single issues and collections. Complete series available to read as part of a DC Universe subscription.

If you haven’t already, make sure to read Part 1 of GCBC’s look at The Long Halloween.

Background (Spoilers Ahead)

If you’re reading this, it’s highly unlikely that you don’t know the fate of District Attorney Harvey Dent. But since Gotham City Book Club is designed to be accessible to new readers, never assuming anything, here’s your chance to stop here and finish reading The Long Halloween. From here on out, no more secrets…

Two-Face was first introduced in Detective Comics vol. #66 (1942, w. Bill Finger, p. Bob Kane, i. Jerry Robinson & George Roussos), under the name “Apollo” Harvey Kent, Gotham City’s young District Attorney and a friend of the Batman. In that same issue, Kent runs afoul of mobster “Boss” Maroni, who attempts to splash the DA with a facefull of acid in court. Batman, Kent’s star witness in the Maroni case, manages to foul Maroni’s aim, but one half of Kent’s face is still permanently scarred.

Alienated from his fiancée Gilda as much as from strangers on the street, Kent becomes obsessed with Maroni’s two-headed silver dollar, the piece of evidence that sealed both their fates. He scratches one side, and vows to make all his choices from now on based on a coin toss. If “good heads” comes up, he makes the peaceful or moral choice. If it’s “bad heads,” he follows his darker instincts towards violent crime. This leads him to confound the public by committing a robbery one day, and then donating to charity the next. Two-Face’s crimes also adhere to a theme, like robbing a double-decker bus or a theatre running a double-feature.

- Two-Face is born in Detective Comics vol. 1 #66 (1942). w. Bill Finger, a. Bob Kane, i. Jerry Robinson & George Roussos

Appropriately, this first Two-Face story was a two-parter, continued in Detective Comics #68, two months later.

Throughout his crime spree, Batman never gives up hope that his friend Harvey can be rehabilitated. In Two-Face’s third appearance in Detective Comics #80, his faith is rewarded as Harvey Kent reforms, risking his life for Batman’s, and is reunited with his beloved Gilda. Harvey even gets a reduced prison sentence and plastic surgery to fix his damaged face. This happy ending would eventually be altered—along with his name, changed to Harvey Dent to avoid confusion with one Clark Kent. Like most of his contemporaries, Two-Face took on a harder edge as Batman stories got darker in the 1970s and 80s, his crimes turning deadlier and less redeemable.

Two-Face got his first Post-Crisis reimagining as part of Secret Origins Special #1 (1989), in a story by writer Mark Verheiden and artist Pat Broderick. Here, Harvey Dent’s ex-wife (this time named named Grace) recounts a different version of Harvey Dent’s life that draws more parallels with Bruce Wayne’s. Like Wayne, Dent loses both of his parents at a young age, but in Dent’s case to an accident rather than crime. Dent gravitates to law because, as Grace puts it, “man’s laws gave order to [his] world.” When, as Gotham’s D.A., Dent learns that the law isn’t enough to defeat organized crime and he’s forced to partner with a vigilante in order to make a difference, it knocks Dent off balance, making him vulnerable to a breakdown when Boss Maroni scars his face in the courtroom. He rejects gray morality and is now only able to do “good” or “bad” things, as determined by the trick coin from Maroni’s trial.

A full, somewhat contradictory origin story followed in 1990’s fantastic Batman Annual #14 (w. Andrew Helfer, p. Chris Sprouse, i. Steve Mitchell, c. Adrienne Roy, l. John Costanza). This 56-page story, entitled “Eye of the Beholder,” is a bold reimagining of Harvey Dent in the tradition of Batman: Year One, and is currently out of print except as part of the Two-Face: A Celebration of 75 Years hardcover collection. While I’ve elected to stick with The Long Halloween for GCBC’s official Two-Face origin, I highly recommend checking this one out at your local library or hunting down the issue online. “Eye of the Beholder” introduces a number of twists to Harvey Dent, such as his history of mental illness, his “lucky” coin as an artifact from his abusive childhood, and his referring to himself in the plural. Some of the specific circumstances of Dent’s tragic disfiguration have their origins in “Eye of the Beholder,” and the character of Vernon Wells from The Long Halloween has a direct analog in “Eye of the Beholder’s” Assistant D.A. Adrian Fields. The influence “Eye of the Beholder” would also reverberate into Batman: The Animated Series, with its two-part episode “Two-Face.”

Over the years, The Long Halloween’s take on Harvey Dent has stood up as the most enduring, becoming one of the primary inspirations for the acclaimed 2008 film The Dark Knight. Upon the release of that film, DC released a new two-part series Two-Face: Year One (w. Mark Sable, p. Jesus Saiz & Jeremy Haun, i. Jimmy Palmiotti, c. Chris Chuckry, l. Sal Ciprioni), a story told in parallel to The Long Halloween. Two-Face: Year One expands on Harvey’s attempts to manage his mental health, as well as his political career, adding the wrinkle that the Holiday murders are taking place during an election year. In this story, rather than turn himself in on Halloween night, Two-Face continues his campaign for District Attorney, as Two-Face. Sable, Saiz, and Haun also dedicate some time to Dent’s friendship with Bruce Wayne. While it doesn’t mesh perfectly with the events of The Long Halloween, it’s a pretty cool companion piece, well worth a read on DC Universe.

Two more Batman villains that we’ve yet to meet in GCBC play a role in the second half of The Long Halloween. The first is Jervis Tetch, The Mad Hatter. Introduced in 1948’s Batman #49 by writer Bill Finger and artist Lew Sayre Schwartz (though not seen again until decades later), The Mad Hatter is obsessed with Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Unlike in The Long Halloween, he’s typically capable of speaking in plain English as well as in quotes from the book, not just the latter. His most famous weapon—mind-control headbands hidden inside fanciful hats—is missing in this story, and he’s mostly here as an accessory to the Scarecrow. Loeb and Sale take a more in-depth swing at The Mad Hatter in their second Halloween special, “Madness.”

Making what is essentially a cameo at the end of The Long Halloween is Oswald Cobblepot, The Penguin. Cobblepot is one of the original Bill Finger/Bob Kane rogues, making his first appearance in Detective Comics #58 (1941). While he eventually grows into one of Gotham’s most traditional gangsters, at this point in the timeline The Penguin is merely one of the city’s best-dressed petty criminals. Cobblepot also makes an appearance in a previous Loeb/Sale Halloween special, 1995’s “Ghosts.”

Both of these characters will get more substantial profiles in future installments of Gotham City Book Club, but for much of the ensemble introduced in last week’s entry, this is goodbye.

Since we focused so much on the partnership between writer Jeph Loeb and artist Tim Sale in the last installment, this time around it’s time to pay respect to the rest of the creative team. Gregory Wright provides the colors for The Long Halloween, as well its predecessors the Legends of the Dark Knight Halloween Specials, and its sequel Dark Victory. Wright began working in the editorial department at Marvel after completing film school in the mid-1980s. This eventually led to a decade-long career as an editor, writer, and colorist at Marvel before he eventually jumped ship to DC. There, he lent color to dozens of issues of Batman, Nightwing, and other DC titles, as recently as 2018.

While not quite as storied as the partnership between Jeph Loeb and Tim Sale, Gregory Wright and letterer Richard Starkings also have a long relationship. Starkings first worked as a letterer at Marvel UK before crossing the pond to New York, where he worked then-editor Wright. Attempting to meet the harsh deadlines of both Wright and fellow editor Bob Harras is what led Starkings to become one of the first letterers to digitize his handmade fonts and begin doing his work by computer. The boom of the early 90s created a lot of business, and inspired him to co-found the digital lettering studio Comicraft, which continues to provide letters for major publishers to this day. Most often, when you’re reading Jeph Loeb’s words in a comic book, they’re written in Starking’s hand, and that’s a small slice of Starkings’ bibliography, to say nothing of the rest of his studio. You can actually buy and license Starkings’ own fonts from Comicraft’s online store, as well as a host of others.

Analysis

The Long Halloween is a 13-issue miniseries built around a murder mystery that ends with very few clear answers. First, Alberto Falcone, believed to be one of Holiday’s victims, resurfaces to take credit for all of the Holiday killings. At least one of them was performed by Harvey Dent as Two-Face, while his wife Gilda tells the reader that she was the original Holiday killer but that Harvey continued her work even before his transformation, all the while unaware that Gilda was the genuine article. Even after multiple readings, it’s clear that no one in the story knows who committed all of the murders.

While some of this is up for debate, here’s how it appears it all went down:

- Halloween—Gilda Dent murders Johnny Viti, the first step in a plan to incite a war between Carmine Falcone, Sal Maroni, and Carla Viti. She hopes that the gangs will eliminate each other, saving her husband the long months and obvious emotional stress of his campaign to bring down the families as District Attorney.

- Thanksgiving—Gilda Dent sneaks out of the hospital to kill the Sullivans’ gang that bombed her house in their attempt to kill her husband.

- Christmas—Gilda Dent kills Milos, the Roman’s chief advisor, to fan the flames of war between Falcone and Maroni. This is the last murder for which Gilda claims responsibility.

- New Year’s Eve—Tired of being looked past, talked over, and kept out of the family business, Alberto Falcone stages his own murder so that he can assume the identity of the Holiday killer. Gilda believes Harvey did this one, but she’s probably mistaken. Alberto’s disappearance and reappearance only makes sense if he really did fake his own death. It’s also possible that Harvey attempted to kill Alberto on New Year’s Eve but that Alberto survived and decided to take advantage of his presumed death to become Holiday himself.

- Valentine’s Day—A group of Sal Maroni’s muscle is shot dead in their car. This one could have been Alberto trying to eliminate his father’s enemies, but it may also have been Dent, who may have devised his own plan to make Maroni so weak and desperate that he’d turn state witness.

- St. Patrick’s Day—More of Maroni’s men bite it. Same story.

- April Fool’s Day—The Riddler is specifically not murdered as an April Fool’s gag. Which of the killers is responsible here is still not clear. On my first reading, I thought Sofia Gigante had done this as a way to scare Riddler, totally detached from the other Holiday killings, and that the real Holiday merely took the day off as a joke.

- Mother’s Day—“The Gunsmith,” manufacturer of the .22 caliber pistols used by Holiday, is killed. This one, I think is more likely to be Alberto. If Alberto was the only active Holiday killer at the time, he may have killed The Gunsmith to protect his identity. If Harvey was also acting as Holiday at the time, the Alberto may have believed (mistakenly) that The Gunsmith was two-timing him by arming the other Holiday killer, and murdered him to try and take exclusive control of the gimmick.

- Father’s Day—Sal Maroni’s father, the retired don Luigi Maroni, is murdered in his garden. Same toss-up as the other Maroni killings, though Harvey seems particularly upset after visiting his own father, who bequeaths to him the trick silver-dollar that becomes the token of his mental illness.

- Independence Day—Alberto Falcone kills the coroner to protect his secret. This is the first actual murder one that’s definitely Alberto, as Harvey has no motive to kill the coroner.

- Carmine Falcone’s Birthday—Alberto Falcone kills his aunt, Carla Viti, at the coroner’s office, where she was presumably about to unearth evidence that his death was faked. Harvey Dent was at large at the time, but was most likely hiding in the sewers where we find him in issue 12, having just fled the hospital.

- Labor Day—Alberto Falcone shoots Sal Maroni in the head while the latter man was being transferred between holding cells. This one’s beyond doubt, as we actually see Alberto kill Maroni. Alberto would later confess to all of the Holiday murders, but we know this isn’t the whole truth.

- Halloween—Harvey Dent (as Two-Face) executes Carmine Falcone, and then his assistant Vernon Wells. Afterwards, he’ll claim “there were two Holiday killers,” but is he referring to himself and Alberto, himself and Gilda, or the two halves of his personality? Is he aware of Gilda’s role as Holiday?

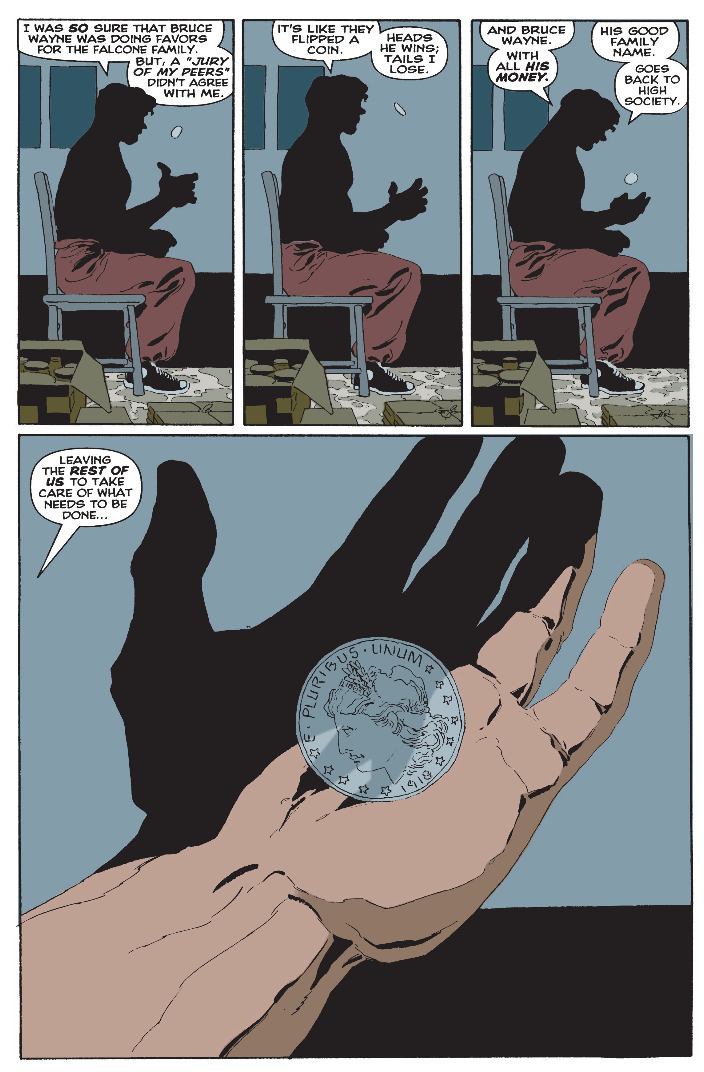

Personally, I tend to think that Harvey was never Holiday until the final chapter, and that his only murders in The Long Halloween are Carmine and Wells. Dent struggles with his faith in the law throughout the series, and I feel it undercuts his journey if he starts killing people any time before Father’s Day, when he seems to turn an emotional corner. Since the next two murders logically have to be Alberto, I think Harvey is innocent up until he becomes Two-Face. That’s just one reader’s opinion. I’m far more attracted to the notion that Alberto Falcone sought to prove his cunning to his father, that he wasn’t a Fredo Corleone (after whom he’s visually modeled) but a Michael, with the added twist of being a bridge between the old mob and the “freaks” who take over Gotham.

And then there’s Gilda Dent. While Alberto being revealed as Holiday is a big twist, it’s possible to have predicted it on your first reading of The Long Halloween. We never see Alberto’s body. The Holiday murders after his “death” tend to be at the expense of Maroni more than Falcones. By the time the coroner is killed, he could definitely be on the reader’s radar. And obviously, given that most readers know going in that Harvey Dent would eventually become a killer as Two-Face, he’s always a suspect from the beginning. But the final three pages revealing that Gilda was the original Holiday killer, while a plausible twist, can seem like it comes out of nowhere.

At least at first…

Gilda has motive. All of her scenes are about her worry that she’ll lose her husband to his job or the darkness it brings out in him. She wants to have a baby with Harvey, but as long as he’s absent and preoccupied, that’s not going to happen. Her motive is tied thematically to part of Holiday’s gimmick—the baby bottle nipple silencer. About half of Gilda’s scenes are set in Barbara Gordon’s kitchen, where Barbara often has a row of them drying on the windowsill. Except as a symbol, the baby bottle nipple serves no purpose—assuming you can accept the premise that a rubber nipple on the end of a pistol could disguise the sound of a gunshot, Holiday fires multiple shots in every single one of their murders, and the nipple would do nothing after it’s broken by the first round. There’s really no point to it being there at all, except to indicate Gilda.

Gilda has opportunity. Holiday always seems to be able to get close to their victims without drawing suspicion, and Gilda is seen as meek and unremarkable. Unlike Harvey or Alberto, none of the victims from the first three Holiday shootings would recognize her.

Does Gilda have the ability to carry out these slayings? Evidentially she does, and a lot more. After her house is bombed, Gilda spends the better part of two months in the hospital, where she apparently exaggerates her injuries to cover her tracks, once again playing on the cultural assumption of her frailty. We see this planted in Issue 3 when she easily leaps out of her wheelchair to embrace Harvey in front of her new home, and then climbs the staircase unassisted.

Both Gilda (a childless housewife who doesn’t seem to have a job) and Alberto (the member of a mob family who’s just faked his death and can’t be seen in public) are in a position to spend hours a day practicing their skills with the murder weapon before beginning their respective killing sprees. They’ve got nothing but time and the element of surprise. And in a series that revolves around a muscular man in a cape jumping off buildings, you can’t really dismiss either of them being the Holiday killer as implausible.

Of course, the Holiday case is only the spine of The Long Halloween’s story—there’s a lot more going on here than just a murder mystery. This miniseries really belongs to Harvey Dent, the hotheaded District Attorney who gradually loses his faith in the law as the city around him comes unglued. From the first chapter, Dent is already exhausted from at least a few years of fighting uphill against the Falcone crime family, who have an answer for every legitimate recourse he has against them. They bribe cops and judges, threaten witnesses, have total impunity to run their business in Gotham, and this is after two years of Batman.

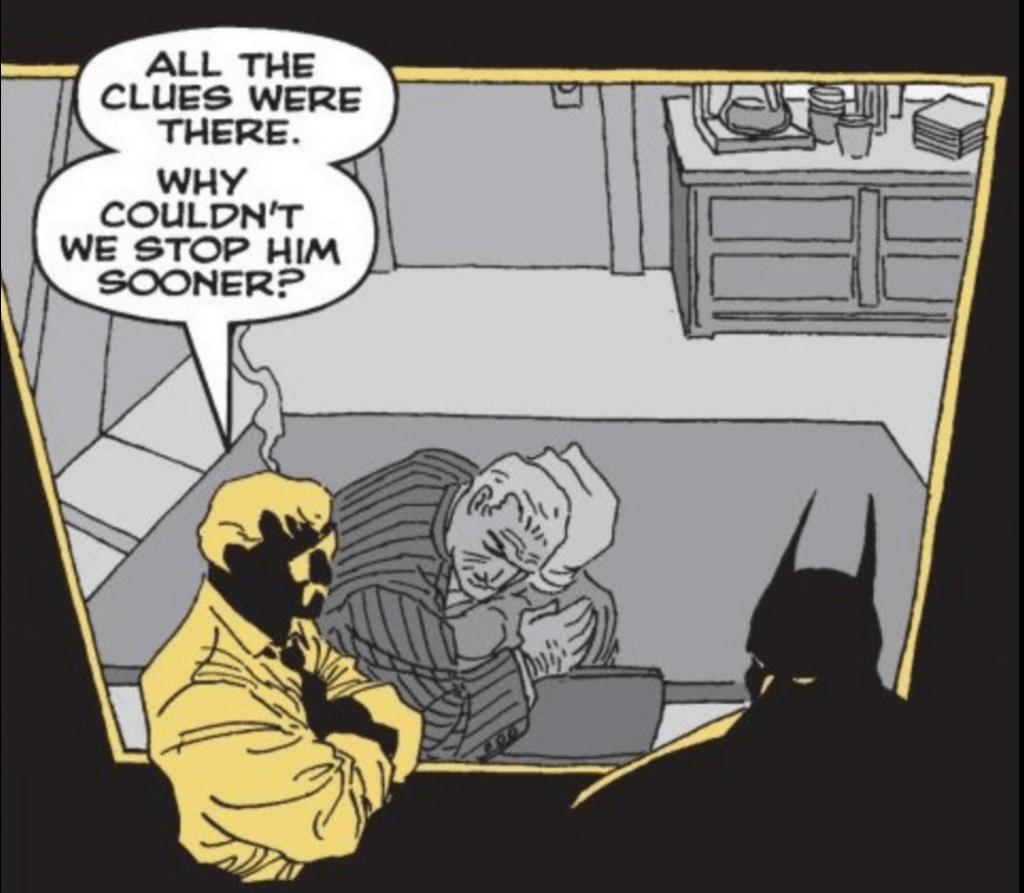

Dent has halfway had it with the law by the time the story begins, leading to his entering into a pact with Batman and their mutual friend Captain Jim Gordon. They each have their own idea of what lines can be crossed and what can’t. Batman will steal evidence, but won’t plant it; he’ll dangle a mobster over a deadly precipice, but he’ll never drop him. Gordon’s already made the only compromise to his values that he’s willing to make by cooperating with a vigilante in the first place. But with Dent, no one’s exactly sure where his line is. He wants Falcone’s empire toppled, but doesn’t seem to care much how that’s done. Gordon has to rein him in repeatedly throughout the year, something he no longer has to do with Batman (for however much good that ever did).

How much does Harvey Dent really even change during The Long Halloween? There’s a quiet rage in him from the beginning that just simmers, and even after he’s scarred he never “blows up,” exactly. Loeb and Sale don’t depict Dent as obviously mentally ill, though on Father’s Day we learn that his father is “crazy.” Harvey doesn’t seem to be losing his grip so much as losing his patience, as lead after lead in the Falcone case fails to cut through The Roman’s defenses. Ironically, the thing that seems to exhaust Dent the most is failing to connect Bruce Wayne to Carmine Falcone, which didn’t fail due to corruption but because there really was no criminal connection.

While the core story of The Long Halloween is palpably decompressed throughout the 13 issues, most chapters contain their own character-focused subplots. The Mother’s Day and Father’s Day issues feature Bruce Wayne’s remembrances of Martha and Thomas, respectively, though as usual Martha gets a bit of the short shrift.

As mentioned in the previous installment, The Long Halloween is a visual feast, and while Tim Sale’s pencils and inks get the bulk of the credit, Gregory Wright also deserves praise for his colors. Throughout The Long Halloween, Wright manages to keep the balance between the sepia-tone of 70s neo-noir and the crazy quilt of superhero comics. The tug of war between the traditional gangster and the bizarre supervillain is a clash between color palettes, and Wright both accentuates that difference while marrying the two worlds together. Something as simple as knowing when to color and when not to color makes a tremendous difference in a story as stylized as this one. The importance of his contribution can be directly measured by comparing full-color printings of The Long Halloween against the black-and-white version published under the Batman: Noir banner.

Over 20 years after its completion, The Long Halloween stands as one of the most impactful Batman stories of all time. Its reverberations have been felt far beyond comics, inspiring the style and characters of the Dark Knight trilogy, the Gotham TV series, and an upcoming two-part animated movie adaptation of its own. If someone has only read one or two Batman comics in their life, the odds are good that The Long Halloween is one of them.

But The Long Halloween is an important in-universe milestone, as well—this is the end of the “Year One Era,” and the beginning of a new, more otherworldly Gotham far removed from the world we know. There will be times when the tone of contemporary comics brings us back to a more stripped-down, grounded presentation of Gotham City, but after the events of The Long Halloween, the cast and scale of Batman’s world never gets any simpler. Soon, the rooftops will be littered with capes and masks playing out an endless ballet of triumph and tragedy, fighting madness with madness, forever and ever.

Thank you for joining Gotham City Book Club. GCBC will return in early 2020 with Season Two: Golden Years.